Just An Old Sweet Song

Out of the blue, son John sent me a link to a song he had just discovered. John has exquisite taste in both music and baseball, so imagine my delight when the link was to my own favorite baseball song: “Van Lingle Mungo”, by Dave Frishberg.

Here it is: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nKzobTlF8fM

Dave Frishberg struck a chord with baseball fans

I hadn’t heard it for a while, so the memories came rushing back, which is kind of the purpose of the song. Frishberg, a talented composer and pianist with a voice that goes with dessert, had first written the song in 1968 to consummate his own love of baseball—it’s basically a roster of mellifluously-sounding major leaguers from the ‘30s and ‘40s that spins around a Dodger righthander named Van Lingle Mungo. With that name and an arm that elicited comparisons to Walter Johnson, Dazzy Vance and Rube Marquard, he certainly deserved to be remembered.

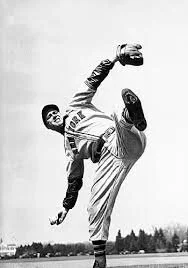

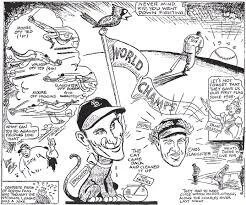

Van Lingle Mungo was poetry in motion

I knew many of the names because of an addiction to Strat-O-Matic Baseball, which put out historical card sets in addition to seasonal sets. That addiction subsided, but not the affection for the song, which I have on vinyl. My wife and I actually went to see Frishberg perform at a New York City nightclub back before any one of our kids were born, and I remember chatting with him between sets.

At the time, I wrote for Sports Illustrated. In fact, one of my very first SI stories was about a hard-luck Phillies pitcher he mentions in the song: Hughie Mulcahy. His official nickname in the Baseball Encyclopedia is “Losing Pitcher” because Phillies box scores often ended with the line: “Losing pitcher—Mulcahy.”

Frishberg had plumbed The Baseball Encyclopedia for the names, some of which are delightful rhymes; Max Lanier and Johnny Vander Meer; Barney McCosky and Hal Trosky, Lou Boudreau and Claude Passeau. The names predate the 1947 integration of baseball by Jackie Robinson, but they are a tribute to immigration—there are players of Italian, French, Basque, Dutch, Polish, Lithuanian, Bohemian, Slovakian, German and Cuban descent.

At least one claimed to have Native American blood.

The tune itself is as captivating as Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “The Waters of March,” which is also a poetic series of images. “Van Lingle Mungo” is certainly superior to the annoyingly, cloyingly popular “Talkin’ Baseball” by Terry Cashman.

A member of SABR, Frishberg has written tunes about Christy Mathewson and the Chavez Ravine Dodgers. But he was more than just a novelty act. His songs have been performed by the likes of Mel Torme, Rosemary Clooney, Diana Krall, Michael Feinstein, Blossom Dearie and Anita O’Day. He also gifted us with “I’m Just A Bill” for Schoolhouse Rock!:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FFroMQlKiag

As for the song I now can’t get out of my head, I followed it down the rabbit hole to find out more about the players he sings about. So forgive me because this story is really long. (Forgive John, too, for opening the can of worms.). But it does go to prove something I’ve always strongly believed. Everybody has a story. I can’t tell you how many idea meetings I’ve attended in which an editor will dismiss a proposed profile because that person is “boring” or “not interesting.” Says who? Those aren’t just names. They’re people, and fascinating people at that. Four of them had sons who played in the majors, and another one had a namesake grandson who made The Show. There’s enough musical talent—at least three of them played the violin—that they could have provided an orchestra behind Frishberg.

Bill Nowlin of SABR has compiled a wonderful companion to the players in the song, as well as a bio of the singer and composer:

http://sabr.org/bioproj/category/completed-book-projects/van-lingle-mungo/

Anyway, here’s Frishberg’s team, trotting out onto the field for Opening Day:

Heeney Majeski, Johnny Gee

Hank Majeski was a great fielding third baseman who hit .310 with 12 homers and 120 RBIs for the 1948 Philadelphia Athletics. He picked up the nicknames Heeney and Shorty while growing up on Staten Island. Shortly after his father passed away when Hank was 8, he was given a baseball glove from a man whose son had just died. “Now you take it,” the man said, “and become a big leaguer.”

Hank set the record for fielding percentage by a 3B in ’47.

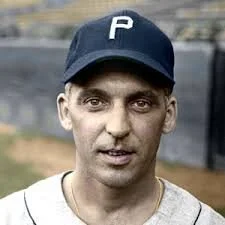

Johnny Gee, a 6’9” lefthander, was the tallest major leaguer in history until Randy Johnson came along. He is also one of only 13 players to play in both the NBA (Syracuse Nationals) and major league baseball (Pirates, New York Giants). With a name like that, and a height like that, his nickname came naturally: “Whiz.”

Gee played with the Nats—the Syracuse Nationals, 1955 NBA champions

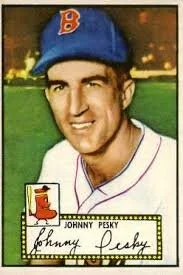

Eddie Joost, Johnny Pesky, Thornton Lee

Joost, a light-hitting infielder who was on the 1940 World Series-winning Redlegs, played 17 years in the majors. As the last manager of the Philadelpha A’s, he was responsible for hiring the first Black coach in the majors, former Negro Leagues star Judy Johnson.

Thanks to Eddie, the ’49 A’s turned a record 217 DPs

Pesky spent 61 years with the Red Sox as a shortstop and third baseman, a manager and a coach. It was for him that the right field foul pole at Fenway Park is named, coined by former teammate and broadcaster Mel Parnell, who recalled that the left-handed-hitting Pesky won a game for him by hooking a homer around the pole.

A pretty good hockey player, “The Needle” once skated with the Bruins

Lee was a two-time All-Star pitcher for the White Sox and the AL ERA leader in 1941. He’s also one of the four players in the song whose sons went on to the play in the majors. In fact, when Ted Williams homered off his son, Don Lee, the Splendid Splinter became the first player to homer off a father and a son in major league history.

The lefty Lee went 22-11 in ’41 with 30 (!) complete games.

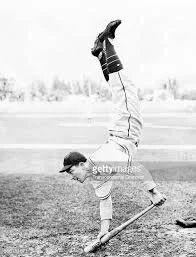

Danny Gardella

Danny Gardella played only three seasons in the majors, but the 5’7” outfielder left a lasting impression. First of all, he could walk on his hands, which he did to amuse Giants fans before games. More importantly, he and a few other players challenged the reserve clause after commissioner Happy Chandler banned them for jumping to the Mexican League in 1946.

“The Mighty Midget” couild also quote Plato and sing arias.

Van Lingle Mungo

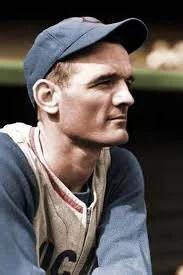

Mungo, whose mother’s maiden name was Lingle and whose father was a cotton farmer in Pageland, S.C., made three All-Star Games, but he never quite lived up to his potential, finishing with a career record of 120-115 and an ERA of 3.47. As his Dodger skipper Wilbert Robinson put it, “He hasn’t the best disposition in the world.” He also had a little drinking problem.

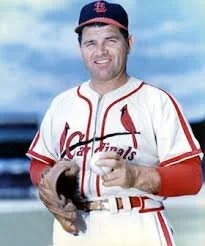

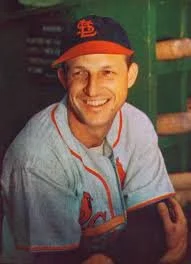

Whitey Kurowski, Max Lanier

You would be hard-put to find a tougher player than George Kurowski. As the 7-year-old son of a Reading, Pa. miner and the sixth of 10 children in his family, he fell off a fence onto broken glass and ended up with blood poisoning in his right arm. Doctors thought they might have to amputate the arm, but instead, they cut a few inches of bone out. He made up for the shorter arm by making it stronger, although he still had to crowd the plate and risk getting hit by inside pitches. Despite that handicap, the third baseman and his fellow rookie Stan Musial turned the St. Louis Cardinals into world champions—it was Kurowski’s homer off the Yankees’ Red Ruffing in Game 5 that gave them the title in 1942.

After winning the ’42 title, tousled the flowing mane of Commissioner Landis

Lanier overcame a similar obstacle. Growing up in central North Carolina, Max broke his right arm twice, the second time so badly that he became a left-handed pitcher at the age of 12. There wasn’t anything Max couldn’t do—he played semi-pro basketball, the guitar and a harmonica, and he had a beautiful “moaning, mountain hillbilly voice.” He also had a son, Hal, who played infield in the majors and managed the Astros to the 1986 NL West title.

Max provided gas for The Gashouse Gang.

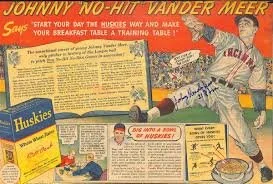

Eddie Waitkus and Johnny Vander Meer

On the surface, Waitkus was a slick-fielding, left-handed-hitting first baseman for the Cubs, the Phillies and the Orioles. But he also played a part in the making of two classic baseball movies. The first was Pride of the Yankees—Waitkus was playing for the Los Angeles Angels, a Cubs farm team, when the movie was being filmed, and because Gary Cooper wasn’t a good enough player to imitate Lou Gehrig, the hitting and fielding scenes were done by Waitkus. The second was an accident, and a shocking one at that. On June 14, 1949, Waitkus was shot in Room 1297A of the Edgewater Beach Hotel in Chicago, where his Phillies were staying, by a deranged fan named Ruth Steinhagen. The incident inspired Bernard Malamud to write the 1952 novel, The Natural, which was later made into the 1984 movie starring Robert Redford as Roy Hobbs.

Waitkus recovered to help the 1950 Whiz Kids get into the World Series

All Johnny Vander Meer did was become the only pitcher in baseball history to throw back-to-back no-hitters. The Reds lefthander was only 23 when he no-hit the Boston Bees on June 11 and the Dodgers on June 15. Vander Meer couldn’t live up to that auspicious start and finished his big league career with a record of 119-121. But even after Vander Meer’s major league career had ended, he kept pitching—when he was 37 and and a player-coach with Tulsa, he threw another no-hitter.

Huskies—The Breakfast of Pitchers Who Throw Back-To-Back No-Hitters

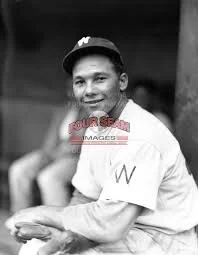

Bob Estalella

When legendary Senators scout Joe Cambria heard about a promising Cuban player named Roberto Estalella, he made arrangements to have him sent to the minor league club he owned. Which is why Estalella had this message pinned to the ticket on his coat when he got off the boat in Key West: Albany, New York. Please Deliver To The Ballpark. As it turned out, Estalella also delivered, hitting .282 over nine seasons with the Senators, St. Louis Browns and Philadelphia A’s. His grandson, Bobby Estalella, had a well-traveled career as a catcher and always wore his socks high in homage to his abuelo.

Bob Estalella paved the way for other Latino ballplayers, including his grandson

Van Lingle Mungo

This story may be apocryphal, but it’s a good one. Once, when the Dodgers were training in Cuba, Mungo fell in lust with a nightclub dancer, who returned his affections. Unfortunately, her husband saw them and Mungo punched him in the eye, upon which the husband returned with a butcher’s knife. Dodger executive, Babe Hamberger rescued him by hiding him in a laundry cart and arranging for a seaplane to whisk him away.

Augie Bergamo, Sigmund Jakucki

The son of Italian immigrants, Augie grew up in Detroit, although he didn’t grow all that much—he was 5’9” and 165. But his athletic skills were such that he was a gifted basketball player, a table tennis champion and a pitcher-turned-outfielder who survived two Cardinals tryout camps to earn a spot in their farm system. He filled in for Stan Musial when The Man joined the war effort.

Augie was the man called upon when The Man was called upon.

Bergamo and Jakucki were on opposite sides of the field when the Cardinals played the Browns in the ’44 World Series. It was the Browns’ only appearance in the Series, and they were there because Jakucki had six-hit the Yankees to win 5-2 and clinch the pennant. Jakucki was hung over at the time. By all accounts, he was a mean sonofabitch who smoked and drank to excess. How mean was Jakucki? He delighted in tormenting the Browns’ one-armed outfielder Pete Gray.

Jakucki also hoisted a few with his right arm.

Big Johnny Mize and Barney McCosky

Mize is the first of four Hall of Famers in the song, and the first of two with a feline nickname. How good was The Big Cat? In 1947 he hit 51 home runs for the Giants and struck out only 42 times. Mize liked to use different bats for different occasions, Said one Giants teammate, “We take two trunks of bats with us on the road. One for The Big Cat, and one for the rest of us.”

The Ruthian Mize was actually the second cousin of The Babe’s wife, Claire

Imagine how happy Barney McCosky was during his rookie year with the Detroit Tigers in 1939. He was playing in his hometown, patrolling the outfield behind his childhood idol, second baseman Charlie Gehringer, and batting second in front of Gehringer with a lefthanded stance he had borrowed from him. McCosky batted .311 that year and became so popular that he was called Detroit’s DiMaggio. The next year, he helped the Tigers get into the World Series by hitting .340 with an astounding 19 triples. To this day, there’s a sports organization in the Motor City called the Barney McCosky League.

McCosky finished second to Ted Williams for the 1947 AL batting title

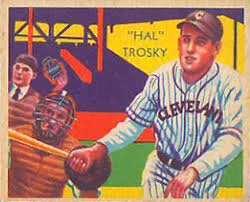

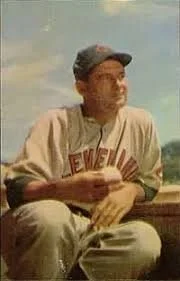

Hal Trosky

Actually, his last name was Trojovsky, so it’s a good thing he changed it from the original, or else he might not have made the song. He was lucky to be found by the Indians in the tiny town of Norway, IA, but unlucky to find himself in an era of Hall of Fame-caliber first sackers. Because his contemporaries were Lou Gehrig, Hank Greenberg and Jimmie Foxx, Trosky never made an All-Star Game—this despite the fact that in 1936, he hit .343 with 42 homers and a league-leading 162 RBIs. He also produced a son, Hal Trosky Jr, born two days after that season ended. Twenty-two years later, Hal Jr. pitched in the majors for the Chicago White Sox.

The dairy farmer suffered from migraine headaches traced to an allergy to dairy products

Augie Galan and Pinky May

Much like Kurowski and Lanier, Galan suffered an accident as a child that forced him to compensate—he fell out of a tree when he was 11 and broke his right elbow without telling anybody about it. Called “Goo Goo” because of his big round eyes and the alliteration of his last name, the speedy centerfielder was immensely popular with both teammates and fans.

Galan should have hit cleanup—his French parents owned a laundry

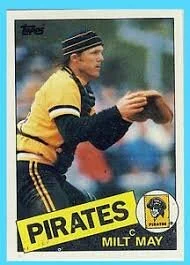

Pinky May got his nickname because of his rosy cheeks. When the third baseman was with the Phillies, his roommate was outfielder Ernie Koy, an interesting pairing given that they would have sons who became pro athletes—Koy’s son Ernie Jr. became a star running back for the New York Giants and Pinky’s son Milt had a 15-year major league career as a catcher. Pinky and Milt actually faced one another when Dad was a minor league manager—after Milt hit two homers on back-to-back nights, Pinky ordered his pitcher to throw at him. Needless to say, Mrs. May was not happy.

Milt once gave his father a spanking

Stan Hack and Frenchy Bordagaray

It’s a shame Smiling Stan isn’t brightening up Cooperstown. For one thing, his 16-year career with the Cubs merits inclusion in the Hall of Fame and 2) there are simply not enough third baseman on the roster. He had a lifetime average of .301, and his on-base percentage was the highest of any modern third baseman until Wade Boggs came along. In 1945, at the age of 35, Hack had his best season, willing the Cubs into the World Series against the Tigers by batting .323 with 99 walks and 12 stolen bases. In Game Six, his 12th inning double staved off elimination. But then they lost Game 7, and Cub fans lost their smile.

That smiling face belongs on a plaque in Cooperstown

Frenchy is the answer to this trivia question: “Who is the only major leaguer to wear a mustache between Wally Schang in 1914 and Reggie Jackson in 1972?” Bordagaray unveiled it to his Dodger teammates in the spring of 1936. He had grown it for a bit part he had in The Prisoner of Shark Island, directed by John Ford after the 1935 season. Bordagaray is uncredited in the movie, but he was a character, alright—he went from entertaining Brooklyn’s “Daffiness Boys” to playing the fiddle and washboard in Cardinal Pepper Martin’s Mudcat Band. From there he went to Cincinnati, where he parlayed a cameo in the ’39 World Series into a nightclub called Frenchy’s Barn.

Frenchy’s mustache kind of grew on his teammates.

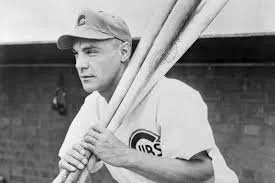

Phil Cavaretta, George McQuinn

Cavaretta was as much a part of Wrigley Field as the ivy. He grew up not far from the park and used to clean up after games in exchange for free passes. He was so small when he showed up for a tryout there at 17 that the Cubs thought he was a batboy. But in his first start at Wrigley on September 25, 1934, he hit a homer that gave the Cubs a 1-0 victory over the Reds. For the next 20 years, he was a Cub, making the All-Star team four times and helping them get into the World Series three times. He had grown up worshipping Lou Gehrig, so he was thrilled when he found himself standing on the first base bag next to Lou in the ’38 Series. “I like the way you play,” Gehrig told him. “Don’t change.”

Cavaretta was the NL MVP in 1945, when he hit a league-leading .355 with 97 RBIs

George McQuinn’s greatest claim to fame wasn’t his seven All-Star Games at first base, or helping the 1944 St.Louis Browns get into their only World Series, or his stellar year with the 1947 world champion Yankees. No, it was the fact that a George McQuinn Rawlings Trapper Claw first baseman’s mitt spent four years in the Oval Office. It was George H.W. Bush’s favorite glove, the one he used when he played baseball at Yale, and he kept it in a drawer of his desk. At crucial meetings with his advisors, President Bush would take the glove out of the drawer and pound his fist into it.

The First Baseman-In-Chief with his George McQuinn mitt

Howard Pollet and Early Wynn

There must have been something in the New Orleans water. How else can you can explain adjacent houses producing one lefthander, Howard Pollet, who would win 20 games twice, and another lefthander, Mel Parnell, who would win 20 games twice. They both pitched in the 1949 All-Star Game, Pollet for the Cardinals, and Parnell for the Red Sox. Unfortunately, they were both shelled.

Howie helped the Cards win the Series as a pitcher (’46) and as a pitching coach (’64)

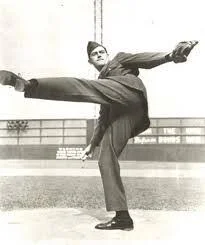

Earl Wynn Jr., 17 years old, showed up at a Washington Senators tryout camp in Sanford, FL in 1937 dressed in coveralls and didn’t walk off the mound until 1963, when he was 43 and wearing an Indians uniform. In between, the righthander recorded 300 victories, intimidated two generations of hitters and hit with power from both sides of the plate. Quite simply, he is the most appropriately named player in major league history.

Early and late—Wynn pitched in four decades, from age 19 to age 43

Art Passarella/Roy Campanella

In an early version of the song, Frishberg sings out Passarella, an American League umpire who later appeared in movies and TV series. Even as an arbiter, he had a flair for the dramatic, ejecting 21 players in 11 seasons. One of them was Browns infielder John Berardino, who dropped the second “R” in his last name when he became an actor. He helped Passarella break into show biz, and that led to one of the strangest scenes in soap opera history. Beradino, who had become famous for playing Dr. Steve Hardy on General Hospital, asked Art to play a patient in a 1963 episode in which the character of brain surgeon Dr. Aloysius Sweeney was played by Yogi Berra.

The Hardy Boys—Passarella, Beradino and Berra

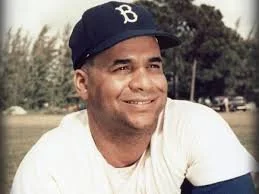

You can’t blame Frishberg for replacing Passarella with the man they called Campy. Had it not been for the segregation that kept Roy out of the majors until 1948 and the tragic auto accident in January of 1958 that left him paralyzed, the stocky son of Philadelphia’s Nicetown might be known as the greatest catcher of all time. As it was, he made eight straight All-Star Games, played in five World Series and won three MVP Awards (1953, ’55 and ’57). His numbers in ’55 are so extraordinary, they make you laugh: .312, 41 homers and a record (to this day) for RBIs by a catcher, 142. As it happened, Campanella had something in common with Art Passarella. Sitting in his wheelchair, he appeared in an episode of Lassie, coaching Timmy’s baseball team.

Campy wasn’t just a hitting catcher—he threw out 57.4% of would-be base-stealers.

Van Lingle Mungo

Yes, him again. On May 16, 1937, Mungo was pitching for the Dodgers in Boston when a giant dirigible flew over Braves Field, causing quite a stir. Mungo’s four-game win streak came to an end, and so did the Hindenberg. It burst into flames later that day in Lindenhurt, NJ. Oh, the humanity.

Too soon?

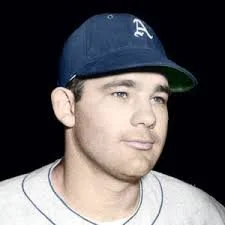

John Antonelli, Ferris Fain

No, not Johnny Antonelli, the one-time 20-game winner for the New York Giants. This is JOHN Antonelli, who had a cup of coffee (grande) as an infielder (mostly third base) for the Phillies in 1945. He hit a respectable .256 in 125 games for the Phils that year but never returned to the majors. He did become a valued coach in the Mets’ farm system—the ’86 Mets had such noted Antonelli pupils as Wally Backman, Lenny Dykstra, Lee Mazzilli, Mookie Wilson and Darryl Strawberry.

Antonelli’s cup of coffee with the Phils turned into a whole pot for the Mets.

As befitting the son of a Kentucky Derby jockey, Ferris Fain had quite a ride. The first baseman was a two-time AL batting champion with the Philadelphia A’s, a five-time All-Star and a superb glove man. But he was also a man who liked a fight and loved a drink, and he spent a chunk of his last days in prison for running a marijuana farm. Asked why he did it, he said, “I grew ‘em because, damn it, I was good at growing things, just like I was good at hitting a baseball.”

Fain had a lifetime OBP percentage of .424—the 13th highest in MLB history

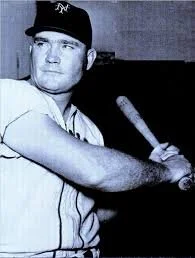

Frankie Crosetti, Johnny Sain

What do you do with 17 World Series rings? That’s how many Frankie Crosetti was entitled to after playing 17 years at shortstop for the Yankees and coaching third base for them for another 20 seasons. At some point, the club gave him an engraved shotgun instead of the jewelry.

Frankie Crosetti touched them all, Ruth to Jeter

Long before “Van Lingle Mungo,” Johnny Sain inspired verse. This is what Boston Post sports editor Gerald Hern wrote on September 14, 1948:

First we’ll use Spahn, then we’ll use Sain,

Then an off day, followed by rain.

Back will come Spahn, followed by Sain

And followed, we hope, by two days of rain.

For a pitcher from the tiny town of Havana, AK, Sain had a big hand in a lot of baseball history. While playing in a war relief exhibition at Yankee Stadium in 1943 for his North Carolina Pre-Flight Cloudbusters, Sain became the last pitcher to face Babe Ruth in an organized game. Four years later, he became the first pitcher to face Jackie Robinson in a major league game. Between ’46 and ’50, he won 20 games four times, with a high-water mark in 1948 of 24-15 with an ERA of 2.60 in 314.2 innings. He pitched in one Series for the Braves and three for the Yankees (1951-53). And when he was through pitching, he became the best pitching coach in the game, tutoring 16 20-game winners and 31-game winner Denny McLain.

Batters prayed they wouldn’t have to face Warren Spahn and Sain in ‘48.

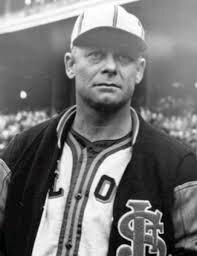

Harry Brecheen and Lou Boudreau

God bless sportswriters. Just as Sain’s name became etched in history because of a newspaper poem, Brecheen’s posterity owe much to his nickname, “The Cat,” coined by Cardinals writer Ray Stockton to describe the lefthander’s uncanny fielding ability. It wasn’t just hyperbole: in 12 years, or 1,906 innings, Harry “The Cat” made just 8 errors. He didn’t make his first start in the majors until he was 28. But he made up for lost time by helping the Cardinals get into three World Series in four years. The third one, in 1946, was The Cat’s Meow: He shut out the Red Sox 3-0 in Game Two, staved off elimination with a 4-1 complete game in Game Six and picked up the win in Game 7 in relief.

“The Cat” had another life, as the pitching coach of the Orioles’ 1966 championship team

What were you doing when you were 24 years old? When Boudreau was 24, he finished his third year as the starting shortstop for the Cleveland Indians, helped coach the University of Illinois’s men’s basketball team and became the Indians’ player-manager. How about 31? Lou was that age when he batted .355 with 18 homers and 106 RBIs while leading the ’48 Indians to the title—hell, in the AL playoff game at Fenway Park, he went 4-for-4 with two solo home runs while holding Ted Williams to a measly single with his patented “Boudreau Shift.” At 51, Boudreau was doing play-by-play for the Chicago Bulls, sharing the Cubs booth with Harry Caray, providing color on Blackhawks game and accepting congratulations on the 31-win season by his son-in-law, Denny McLain. Two years later, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. You could say Lou Boudreau was a baseball man for the ages.

Red Sox manager Joe McCarthy congratulates Boudreau after their 1948 playoff game.

Frankie Gustine and Claude Passeau

Frankie Gustine wasn’t exactly a Hall of Fame player. In 12 seasons, 10 of them with the Pirates, the infielder had a lifetime average of .265 and never hit double digits in home runs. But a string of Hall of Fame players loved watching him play because of his competitive spirit and versatility. There was Pie Traynor, who discovered him. And Frankie Frisch, who made him the Pirates second baseman. And Honus Wagner, who tried to set Gustine up with his daughter. And Ralph Kiner, who roomed with him. And Jackie Robinson, who said of Gustine and teammate Hank Greenberg, “You won’t find two finer fellows in baseball.” And Roberto Clemente, Bill Mazeroski and Willie Stargell, who stopped by his popular restaurant near Forbes Field.

A matchbook from Frankie’s establishment, which finally closed in 1982.

Imagine this scenario. You’re the starting pitcher in Game 3 of the 1945 World Series. Your team, the Chicago Cubs, is facing the Detroit Tigers, who once released you because they didn’t think you’d ever make the major. The Series is tied at one game apiece and the crowd of 55,000 at Briggs Stadium is rooting against you. Oh, and the guy batting sixth for the Tigers, Rudy York, was once your roommate in the minors.

What Claude Passeau did in that situation was pitch one of the greatest games in World Series history. The righthander with a left hand that was crippled in a childhood hunting accident shut out the Tigers on one hit, a second-inning single by his ex-roomie. Passeau also drove in the Cubs’ final run in the 3-0 victory with a sacrifice fly. Not only did Chicago rejoice, but so did Mississippi, where Passeau was born and raised. He settled down on his 600-acre farm in Lucedale and became the county sheriff. Kinda figures. He once locked up the entire city of Detroit.

Passeau often showed up late to camp because he was busy planting.

Eddie Basinski

Eddie was such an unlikely ballplayer that he once made Ripley’s Believe It Or Not.

He was a violin virtuoso who held a chair in the Buffalo Symphony Orchestra when he was a high school freshman. He hadn’t played in high school, college or the minors when he made his major league debut—the Dodgers found him in a semi-pro league. A graduate of the University of Buffalo in mechanical engineering, Basinski wore such thick glasses (owing to a bout with scarlet fever as a child) that Branch Rickey said he looked like “an escaped divinity student.)” But “The Fiddler” could play. Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber would accompany another marvelous play at shortstop by Basinski with, “The violin is playing sweetly today.” He even made the Associated Press All-Star Team in ’45.

After the Pirates released him after the ’47 season, Basinski went on to play for the Portland Beavers for 11 years. He settled in Portland, raised a family and worked as an accounts manager for Consolidated Freightways for 31 years. Although he’s now in an assisted living facility, he can take pride in the fact that he’s the third oldest living major leaguer. And that he played both baseball and the violin very sweetly.

The Fiddler entertains some of his Portland Beavers teammates.

Ernie Lombardi

What took so long? Because catcher Ernie Lombardi was as slow as he was big, he needed some time to get to first base, and opposing managers stationed their infielders on the outfield grass to take advantage of that. Even with those handicaps, “Schnozz”, or more poetically, “The Cyrano of The Iron Mask”, led the National League in batting average twice and batted .306 over his 17 seasons. Which leads to another question:

What took so long? Why did it take until 1986, nine years after his death and 39 years after his last at-bat, for Lombardi to be inducted into the Hall of Fame. One glance at his statistics would tell you he was one of, if not THE greatest hitting catcher of all time. From 1935 to 1938, he hit .343, .333, .334 and .342 for the Reds. It would take 69 years after his last batting title for the Braves (.330) in 1942 before another catcher (Joe Mauer) won a league batting title.

And Lombardi wasn’t just a hitter. He had a rifle arm, nimble hands and a keen mind for the game. While hitting .342 with 19 homers and 95 RBIs in his MVP season of 1938, he also called every pitch of Johnny Vander Meer’s consecutive no-hitters.

Better late than never. But the voters were a lot slower than Lombardi was.

Ernie’s hands were so big that he could go 5 (fingers) for 7 (balls)

Hughie Mulcahy

Despite his nickname, Mulcahy was the best pitcher on the ’38 Phillies. He had a no-hitter going against the Reds on September 16 when he flied out to end the seventh. As he was jogging back to the dugout, a lady yelled out to him, “Hughie, it’ll be a no-hitter.” She had broken the sacred vow of silence, and sure enough, Ernie Lombardi led off with a single to start the eighth.

Mulcahy won that game, but he lost 20 others that season for the Phutile Phils. He would lose 22 in 1940, after which he became the first major leaguer to be drafted. It was just his luck.

What I discovered when I interviewed him in 1978 was that he never bemoaned his fate. He lost the prime of his career to the Army, but he was grateful that he had survived the war and found employment in baseball afterwards. What I remember is what a nice man and what a great sport he was. This is what I wrote:

Had I been a better reporter, I would have discovered and added one more of his accomplishments. In 1955, one of the many years he coached in the White Sox system, Hugh invented a catching machine that returned the ball automatically to the pitcher. That way, pitchers didn’t have to find an available catcher to get their work in during spring training. I guess you could also call him “Helping Pitchers” Mulcahy.

Hughie lost four years, 45 pounds and the command of his fastball to the Army.

Van Lingle Mungo

Frishberg and Mungo actually met shortly after the song’s release. It happened on The Dick Cavett Show when Dave performed the song. Mungo asked him if he would receive any royalties from the song, and Frishberg informed him that while he would not, Mungo could get even by writing a song called “Dave Frishberg.”

So thank you, Dave, for striking such a beautiful chord. If you feel as I do, there is a way to express that gratitude. Dave lives in Portland, OR now, and on March 23, he will turn 88. He has some serious health care issues, and his wife, April Magnuson, has set up a GoFundMe page on his website (https://www.davefrishberg.net) if you wish to help him out.

After all, he gave us the gift of music and time.

-30-