“Hear My Sad Story”

There were raised eyebrows when Anthony Hopkins won the Oscar for Best Actor the other night and Chadwick Boseman didn’t, but it’s hard to argue with greatness. Besides, that wasn’t the first or worst snub in Oscar history.

Consider the nominations for Best Supporting Actor in 1974. John Houseman certainly deserved to win for The Paper Chase (“Mr. Hart, here is a dime…”) in a strong field that included Jack Gilford (Save The Tiger), Jason Miller (The Exorcist) and Randy Quaid (The Last Detail). But there was another nominee whose presence was made conspicuous by the absence of an actor from the very same film.

Hindsight is 20-20, of course, but it’s hard to believe that Academy voters who saw Bang The Drum Slowly in 1973 felt that Vincent Gardenia was more worthy of a nomination for his over-the-top comic turn as the manager of the New York Mammoths than the young actor who quietly helped carry maybe the best movie ever made about baseball… and then became maybe the best actor of his generation.

Watch what Robert De Niro does without saying a word while teammate Piney Woods (Tom Ligon) sings the song that inspired the title:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BH6ri4yasfk

Man, I loved that movie then, and I love it still—just as I adored the Mark Harris tale upon which it’s based, the second of his quartet of novels told in the distinctive, authentic voice of lefthanded pitcher Henry Wiggen. I’m not saying it’s maybe the best novel ever written, but it does have this distinction: In the American Book Review’s list of the 100 Best Last Line of Novels, Bang The Drum Slowly comes in at No. 95 with, “From here on in I rag nobody.”

The 1956 novel that touched them all

Where did those words to live by come from?

Mark Harris Finkelstein was born in 1922 in Mount Vernon, N.Y. He wanted to be a journalist, and dropped his last name, but before his career could get going, he was drafted into the Army in January of 1943, then branded as a misfit for his opposition to the racial discrimination in the ranks. Upon his discharge, he went to work for The Daily Item in Port Chester, N.Y., then bounced from newspaper job to newspaper job, New York to St. Louis to Albuquerque to Chicago and back to New York, while writing a novel, Trumpet to the World (1946) about the interracial marriage of a serviceman.

He then immersed himself in academia, which proved to be a better fit. The first Henry Wiggen novel, The Southpaw, was published in 1953 while he was studying for a PhD in American Studies at the University of Minnesota, and the second, Bang The Drum Slowly, in 1956, at the start of a long stint as an English professor at San Francisco State. (There’s actually a character in the novel, Red Traphagen, who’s a catcher turned English professor in San Francisco.)

The cleanup hitter among baseball novelists

There are echoes of Mark Twain in those novels, but there is also a deep understanding of baseball and team dynamics and life itself. Bang The Drum Slowly, with its mixture of humor and heartbreak, was an immediate success that was adapted as a television play for the United States Steel Hour, broadcast on September 26, 1956. If you don’t have time to read the novels, you’ll get a pretty good sense of them, and the additional kick of seeing the young Paul Newman perform live as Wiggen in this video of the production on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h0fdEVTAsf4

There’s so much to chew on in this version. Piney Woods was played by the then-unknown George Peppard, who went on to star with Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961). Clu Gulager, a future star in TV westerns, is in the background, as is the character actor Bert Remsen. The pivotal role of the doomed Bruce Pierson is played brilliantly by Albert Salmi, an actor of Finnish descent who appeared two years later in The Brothers Karamazov—in a cast that included Yul Brynner, Lee J. Cobb, Richard Basehart, Claire Bloom and William Shatner—and then went on to play more than 100 TV and movie roles before becoming a theatre professor.

Batterymates Newman and Salmi

As for Newman, he seamlessly alternates between narrator and player while revealing his humanity in a series of stage scenes that take up less than an hour. Because it was filmed live, you can hear him bobble a name in the last scene, but then he nimbly recovers to nail the last lines of the novel and bring the viewer to the same tears he sheds. (As it happens, the director of the TV production, Daniel Petrie, would reunite with Newman in 1981 for the Hollywood film, Fort Apache, The Bronx.)

Why the title? Long before Harris tinkered with the line, “Oh, beat the drum slowly,” the song called “The Streets of Laredo” haunted American music and culture. Also known as the “Cowboy’s Lament,” it was first published in a 1910 book, Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, and it tells the tale of a young man dying from a gunshot wound who tells a fellow cowboy, “Come sit down beside me and hear my sad story.” His last request is:

“Get six jolly cowboys to carry my coffin/Get six pretty maidens to bear up my pall/Put bunches of roses all over my coffin/Roses to deaden the clods as they fall”

Arlo Guthrie, one of the many artists who have recorded “The Streets of Laredo”, calls it “the saddest song I know.” It’s made even sadder when “Author” recounts Bruce’s funeral: “There were flowers from the club but no person from the club. They coulda sent somebody.”

Harris himself adapted his novel for the 1973 film version, which was directed by John Hancock, who had built his reputation in the theatre and with a wonderful, Academy-Award nominated short about a middle-aged touch football player called Sticky My Fingers… Fleet My Feet. Michael Moriarty was cast as Henry Wiggen, and he had the bloodlines—his grandfather was George Moriarty, a third baseman on the Detroit team that played in the 1909 World Series, as well as a manager for the Tigers and an umpire. But he also had the chops—you can easily buy him as an elite pitcher, a writer, an insurance salesman and a true friend. (Moriarity is right-handed, which Wiggen wasn’t, but his pitching motion is pretty damn good.)

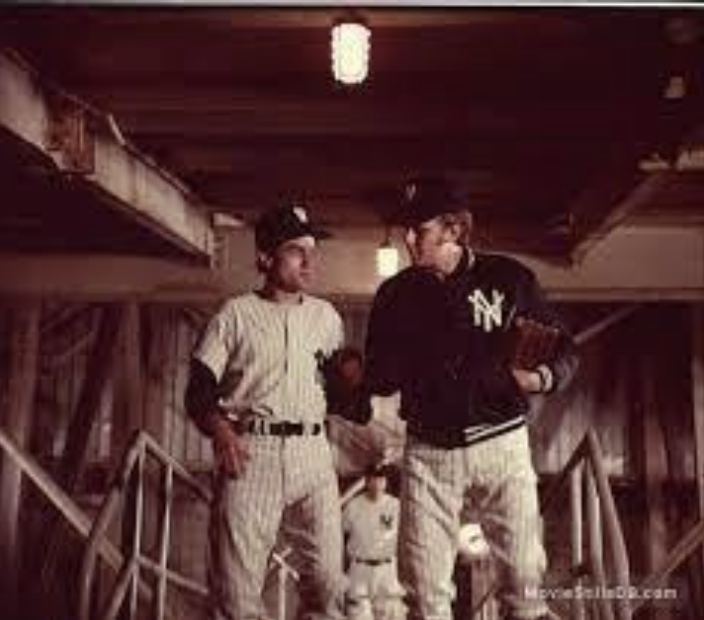

As for De Niro, who had been in Brian DePalma’s cult classic Hi, Mom!, he captures the innocence of a country boy and the fear of a man who’s doomed to die. When it’s just him and Moriarity on the screen—jogging in the outfield, sharing the joy of victory with their eyes, comforting one another in a hotel room—you know that they’ve gone over their signals. De Niro was a revelation then, and 40 years later, you better understand the eight Oscar nominations he did receive.

DeNiro and Moriarity were on the same page

There are other wonderful performances in the film. The comedian Phil Foster is particular good as the coach who teaches Bruce the mysteries of the card game TEGWAR, Selma Diamond does a funny turn as the Mammoths’ switchboard operator and Barbara Babcock, who would win an Emmy for her role as Grace Gardner in Hill Street Blues, takes over the room when she appears as the Mammoths’ owner. It’s also interesting to see Danny Aiello, one of the players, together with Gardenia 14 years before they were in the cast of Moonstruck with Cher, Nicolas Cage and Olympia Dukakis. She and Gardenia both got supporting nominations—she won, but he didn’t, losing to Sean Connery for The Untouchables.

In a 1997 profile of Mark Harris in the Phoenix New Times, he said, “I never talked much to DeNiro.” But he did recall that when the rest of the cast was at dinner while on location in Florida, he saw DeNiro dive into the hotel pool, swim a few laps to invigorate himself, then hurry back to his room to study his lines for the next day’s shoot.

At the time, Harris was teaching in the creative program at Arizona State, where he was a professor for 21 years. In his long, rich life, he wrote 11 novels, 7 nonfiction books (including his own autobiography) and numerous short stories. And that one great line.

Harris passed away in Santa Barbara in 2007 at the age of 87 due to complications of Alzheimer’s. In the New York Times obituary on Harris, the great poet Donald Hall put this rose on his coffin:

“If I had a vote, I would put Henry up for Cooperstown.”

-30-